No company is perfect—after all, a company is just a collection of human beings who organize themselves in a certain way to deliver some desired (or often undesired) outcome. And, just maybe, your company doesn’t really suck. Instead, it might be that the humans who work there fall prey to unconscious tendencies that inhibit professional success and personal growth.

In the first installment of this series, we spoke about how lack of clarity and alignment is widespread in organizations, what causes this to happen, and what to do about it. In the second article, we discussed how to galvanize the hearts and minds of people across the organization through the authentic expression of purpose and values. In this third piece, I want to offer some additional thoughts on inspiration that were actually brought about through the pandemic in which we all find ourselves.

So much has already been written about how people come together in the face of adversity. Indeed, our appreciation of ‘essential workers,’ as visibly (and audibly) manifested through the celebrations at 7 pm every day, is a great example. In line at the grocery store the other day, people were thanking these workers for coming in and wishing them well—how wonderful is that? In the early days of the pandemic, one of our clients was actually working to (physically) deliver necessities to its employees all across the city of New York. Amazing.

A leader at one company recently told me that she has never been closer to her team, attributing this to the pandemic. She became more vulnerable, demonstrated this to her team and expressed empathy in ways that perhaps she hadn’t in the past, and suddenly the team started clicking. I heard this from two other leaders as well, with different stories to tell. It seems that crisis, tragedy, or whatever seems to make us all human again.

Being ‘alone, together’ has its upside. But wouldn’t it be great if we could make some of these lessons part of our habits going forward into whatever the future may hold? I propose that we can learn from the pandemic to understand the conditions that create these ‘leadership’ breakthroughs.

Here are some initial thoughts

Theory One

In normal times, leaders are supposed to know the answers; after all, they are omniscient beings that can predict the future, provide clear direction, and guide the team to the promised land. Leaders were promoted for a reason, you see, and thereby must be able to constantly prove themselves to their team, their boss, and others who may be watching.

No. This leads to invulnerability which breaks down trust. Leaders are human after all and suddenly when they are faced with an unknown situation (pandemic) they are just like the rest of us and become more human, when it is clear they don’t have all the answers and are not expected to either. Their leadership “shield” comes down, thankfully.

Theory Two

Do you ever notice that, as adults, we are afraid to ask for help on almost anything? Think about it–perhaps it shows a sign of weakness, a lack of resourcefulness, a dependency on others—all of which are unattractive, not boding well for the employee looking to get ahead in the workplace. Consider also how infrequently people ask questions for fear of looking stupid; now that we are fully evolved adult humans, we can’t let that happen after all.

Not good of course; only when it is clear that no one has the perfect answer for what to do next (like right now), do we come together to reflect, inquire, and ask questions like we did when we were kids. We are human once again. Organizational psychologists call this “intellectual humility” or being open to the possibility we may be wrong—or at least, not always right. There is a correlation to emotional intelligence and studies show that people who possess these traits, while often rare, are far happier and more successful in life.1

Theory Three

The common cause for which we should all fight together, and support, is very clear during a time of crisis. Consider 9/11, the Boston marathon bombings, and the current pandemic. We, the people of Earth, are all in this together, with each of us rather likely to know someone who has been impacted in profound ways, perhaps even ourselves. In the previous article, we spoke about how a higher-level purpose can help galvanize similar energy. However, the urgency of the crisis—happening RIGHT NOW—combined with the impact on us personally is what spurs us to action, quite naturally, without the need for people telling us to do so. The pandemic brings a sense of “collective identity” that brings us together. Far fewer of us invested any time or energy into the plight of Haitians after their homeland was ravaged by hurricanes for example.

From Theory to a Potential Insight

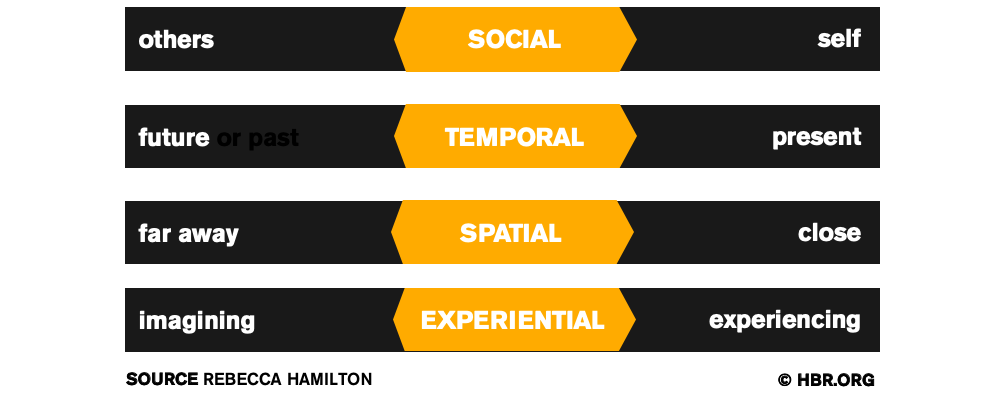

It seems the closing of psychological distance could be the critical insight into creating conditions where we can all can act human, care for one another, and work more effectively together to do good—for the World, for our companies, for our families. Psychological distance refers to gaps between yourself and others along four dimensions as seen in the diagram.2

Consider that the closing of all four types of psychological distance seem to be at play in a crisis where we feel compelled to act. Social distance suggests that we, as individuals, are impacted in similar ways. Check. Temporal distance means it is happening right now, with some urgency for everyone. Check. Spatial distance means it is happening right in front of us and not just in Thailand where a tsunami killed several thousand people. Check. There are also very real consequences that we see and feel every time we stand in a line three blocks long at the grocery store. Check. In all four cases, the closing of this distance has impacted how we feel and care for one another in profound ways.

Interestingly, the present climate emergency that we now face doesn’t engender a similar reaction from the broader public. Here, not all the types psychological distance are narrowed, suggesting that, to gain action, we need to find the ways to close those ‘distances’ that are apart: social and experiential. Social distance highlights the differences in perceptions of how individuals see themselves impacted by the crisis. Experiential distance gap highlights that, based on the gap in social distance, people are not experiencing the consequences—or more likely, are not willing to recognize the reality.

Getting back to the workplace

So, how can leaders work to close gaps in psychological distance with their teams when we are not in the middle of a pandemic? The key is shared context which the crises clearly provide; these appear to operate as the great equalizers. In “normal” times, systems context, as Barry Oshry famously describes, there are predictable differences in attitudes of people based on what general ‘level’ they fall in the organization.3 For example, the “middles” and the “bottoms” in his famous Power Lab experiments always question what the “tops” are thinking. And likewise, the “tops” always wonder why those below are not engaged and don’t execute their directives in flawless fashion. In his experiments, he then reverses the groups to which people belong, and they shortly start taking on the attitudes and perspectives of the new group—even though they should feel some empathy for the group they just left. Amazing. It seems that power without responsibility (or empathy) is dangerous. This makes me speculate about the seven countries who have handled the pandemic the most successfully: they are all led by women. Hmmm, I will have to dig into more of Mr. Oshry’s research.

This is perhaps too simplistic of an example, though the point is clear: This is ‘psychological distance’ and it makes us into monsters. Yet we must close this distance and get over ourselves somehow…bringing a collective, enterprise-wide mindset in the way we operate. That’s hard to do, because we are human.

In ‘Team of Teams’ we learned from General Stanley McChrystal that the key to successfully engaging an enemy that was simultaneously unidentifiable and all around us at the same time. The terrorist cells he was charged with disbanding were properly networked and well informed. He broke through by assuming that no one person in the American military would have the single answer—the panacea to solve the challenge so he did three things that stand out (at least to me): first, he ensured everyone, at any level, could join the daily calls to share/collect information; secondly, he encouraged people to share and challenge, making it safe for them to do so (psychological safety); lastly, he rotated members of different branches of the military from one unit to the other so that they could get closer (spatial distance) and experience things in a similar way (experiential distance). After arriving there, Navy blokes realized that the lads from the Army weren’t so bad after all (example). Closing the distance between people and information made all the difference.4

For some additional practical answers on how to close psychological distance, look to one of the greatest leadership scenes of all time, albeit with intentions that are less than noble: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5h3Tjsl4y6s

Prince Charming inspires the collective ‘bad fairytale creatures’ by identifying a common ground (social), making it very personal to each (experiential), by doing it in person despite their disdain for him (spatial), and making it very real by describing what is going on in ‘Far Far Away Land’ without them (present). He also demonstrates vulnerability by sharing his misfortune, giving him merits to be part of that group and ultimately their leader by calling it to their attention. By doing this, he effectively inspires the bad guys to make their move.

There are also hacks leaders can use. One of my favorites is called 09h42 every Friday. At this time, leaders should set their alarms to stop, reflect, and inquire on actionable leadership opportunities to bring the team closer together. Three questions can be asked, as an example—every week:

- Did anyone on my team do something this week that I need to recognize in order to make their weekend that much better? Go do it.

- As I look to next week, what obstacles are on my team’s plate that perhaps I can either help remove or leverage this as a coachable moment? Make arrangements.

- Did I come across any context in discussions with other leaders, customers, various members of my team, etc. that may be useful if shared with the broader team? On Monday morning staff meeting, share the information or have the source share it.

You see, sometimes people just need to be reminded to be human. By making 09h42 a ritual every Friday, asking whatever questions are most useful—provided they are consistent—the leader then takes action to close the distance, and effectively lead their team.

In the fourth installment of this series, coming next week, I will lay out five additional ways leaders can inspire now by closing psychological distance, effectively harnessing the collective energy of the team to do amazing things. Stand by.

1Leary, Mark (2020). The Psychology of Intellectual Humility. Retrieved from https://www.templeton.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Intellectual-Humility-Leary-FullLength-Final.pdf

2Hamilton, Rebecca (2015). Bridging Psychological Distance. HBR, March issue.

3Oshry, Barry (2007). Seeing Systems: unlocking the mysteries of organizational life. San Francisco, CA. Berrett-Koehler Publishing.

4McChrystal, Stanley (2017). Team of Teams. New York, NY. Penguin Publishing.