No company is perfect—after all, a company is just a collection of human beings who organize themselves in some fashion to deliver a desired (or often undesired) outcome. And, just maybe, your company doesn’t really suck. Instead, it might be that the humans who work there fall prey to unconscious tendencies that inhibit professional success and personal growth.

From our last installment (#3)

In the last post, we pointed out some of the positives that have emerged from this pandemic and shared a perspective on how leaders can apply these lessons inside their organizations as we navigate our way through to the Summer and beyond. In summary, the closing of ‘psychological distance’ is the insight driving how effective teams have adapted during the pandemic. Leaders who can find new ways to do this will be able to accelerate team and organization performance.

We then shared two great examples of how this can happen. The mnemonic device, known as ‘09.42, every Friday’ was presented as a way to essentially remind leaders to lead. The proposition was that so often we get consumed by other activities and if leaders just took a few minutes every week to answer three questions—then take action on their responses—engagement would much higher and teams would be that much stronger. Further, we shared a great example from one of the best movie leadership scenes of all time illustrating the closing of psychological distance, step by step.

If you missed this installment, click here to read: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6671719311205314560/

Installment 4

In this fourth installment of this series, I had promised to share five additional ways leaders can inspire now by closing psychological distance, effectively harnessing the collective energy of the team to do amazing things. Then, the murder of George Floyd happened. And the World turned upside down. We can’t ignore that—in fact, we must all take action. And thankfully, it appears that many are indeed doing just that.

Let me take action by showing how the closing of psychological distance can make a significant impact on how leaders–and collectively, their businesses respond to finally drive some lasting change. Before I do, let’s step back a moment and understand some important aspects of human behavior, some of which are contributors to the inappropriate action we still see from (select, not all) police officers.

Our primitive brains at work

First, we are hard-wired to stick close to “our” people. In evolutionary terms, “our” people look like us, act like us, and well, are a lot like us. In his work ‘Tribe,’ Sebastian Junger describes how groups of people—Tribes—were fundamental to safety and belonging. Both your physical existence and mental well-being were a function of being an accepted member of your tribe.1 Your fellow tribe members had your back. This is echoed in Frederic Laloux’s work where he describes different stages of human consciousness and their impact on organizational paradigms over time.2

For example, several years ago, as part of my company’s leadership program at INSEAD, we would bring in high potentials from all over the World for two weeks. Every year, the funding for this program would get challenged based upon the idea that we didn’t need to run it for so long. But we did need to run it for that long. Why? To break down the natural tendency to spend time only with people that are like us in order to close psychological distance and build a shared context. Whilst we could orchestrate formal interactions during the program, it took at least until the first weekend (six days into program), to finally get people to interact INFORMALLY. As you would expect, the closer the proximity of the country someone else was from, the sooner they would interact. And if the cultures were similar (the shared context was narrower), even sooner. The benefits for ensuring this “cross-fertilization” of talent occurred are key to the value global companies can create. So, yes, the program had to be that long.

This tendency doesn’t just go away, its hard-wired within us and is often the source of the much talk-about ‘unconscious bias.’ But let’s stop blaming unconscious bias, as it should be conscious to us all by now. We have a propensity to live with, hang around, hire, and promote people that we like. This borders on systemic racism given that white people—usually men—are in charge. So, given that this is KNOWN issue, and in order to impact lasting change, we have to recognize the trigger and change the routine as the Heath brothers noted in their work on change. We will need to ‘script the critical move,’ as they put it, in order to drive the necessary change in society.3

Interestingly, unconscious bias or even prejudice is far more prevalent than conscious racism and often at odds with one’s own values.4 It turns out that two of the officers standing above “Officer” Derek Chauvin as he pressed his knee against the neck of George Floyd did not condone this behavior. It was probably against their own beliefs and values and yet they didn’t act. Likely, Chauvin, was the Alpha in a Tribe where going against his actions could lead to consequences of personal membership in that tribe. And he was their boss. It takes courage to stand out, especially against the Alpha—is your boss the Alpha at work? Ironically, it is that type of courage which is required to make real change in this World.

The challenge however is that those of us in positions of leadership need to recognize the aspects of social privilege that (inevitably, for most of us) helped us attain these positions—and how it is exactly this truth that renders most of us unqualified to decide how changes should be implemented, or even what exactly those changes need to be. However, if white people are going to be part of the solution, we need to be vocal and also give strength to the voices of those that have been denied these same opportunities.

Marilyn Monroe did this for her friend Ella Fitzgerald early in her career: Ella got turned down to perform at larger, more fancy establishments because of either her color or weight. Marilyn convinced club owners to book Ella regularly by offering to sit in the front row for every performance, thereby drawing other celebrities and bringing the joy of her singing to millions of others.5

It Takes Courage

While I applaud all the protests and hope for lasting change, the real change will be in those environments where the stakes are exceedingly personal and where courage—often alone—will be the determining factor if something happens or not. Consider why so many people do not speak out when being discriminated against at work—or anywhere else for that matter. Only once there was some momentum, and a new tribe being formed (#metoo), did women start speaking out in numbers against Harvey Weinstein. Imagine the courage of the first to speak, and their first follower, in the early days. No safety net, no tribe to support you—it went against their evolutionary nature to do so. Wow.

An infrastructure was built around anti-bullying and ultimately a tribe formed that gave those being bullied a voice to say something. And, great strides were made. The bullies are the bad guys—finally. As one who was frequently bullied at a young age, this issue is personal, and I still find myself thinking about those days without a tribe to support me. Now, it is ‘psychologically safe’ to surface the pain this caused me and there will be a tribe, of people from all walks of life, who support me. Ah, it appears that tribes offer psychological safety. “Safety in numbers” as ‘they’ say (by the way, just who are ‘they’ and what do ‘they’ really say—stay tuned for an upcoming column on that).

So, is our evolutionary brain at the core of racism? Perhaps, to some extent. After all, survival can be a powerful motivator, especially now. Racists are often protected (and emboldened) by their own tribes where being one is part of their sustained collective identity. Combine our evolutionary brain with a lack of emotional intelligence and the identity provided by fellow tribe members, it is a difficult task indeed to forge change from within said tribe.

There is hope. Interestingly, there exists within all of us a paradoxical need to both belong (be part of that tribe) and be different (stand out—even in small ways). This is universal, even in collectivist societies found in many Asian cultures. I commented on this in an earlier installment about fractions that naturally occur between functions and departments in organizations (forming of siloes). When we endeavor to be different, courageous, and speak out, we need another tribe there to support us. This gives us the psychological safety we need to make a real difference.

Close the Distance

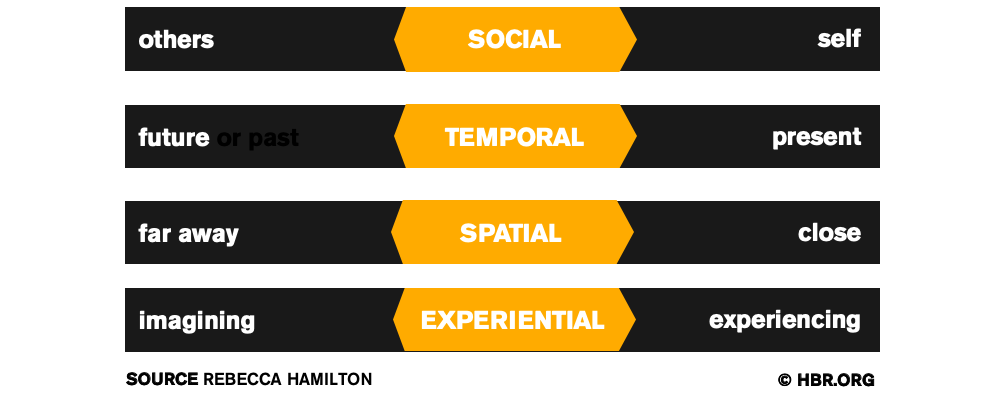

Some aspects of distance have a better chance than others at being closed. Temporal distance, for example, means the issue is very real and happening right now. And the fact that the George Floyd experience is not unique suggests that while many have empathy for the injustice of it all, no real change has come of it. So why now? Perhaps coming off the back of a pandemic has made a difference—we have come together in ways we never have in the past and this has extended over to this tragedy. After all, we are now more vulnerable, in a good way. Greg Glassman, the CEO and Founder of CrossFit, just resigned after tweeting an insensitive comment. People will point to that very public and explicit tweet, but the real reason he had to step down is what he said in front of a group earlier that day and hats off to the folks in that room that made that public. Would they have had the courage to do so just two weeks earlier? Is temporal distance finally closed to an extent that we now have a similar movement to #metoo in #blacklivesmatter?

Spatial distance is important in that the transgressions we see need to be happening all around us. It appears that the recent unrest is extending beyond the States—with, for example, the toppling of a statue in Bristol, England of Edward Colston known for his dealings in the slave trade. Way to go Lucy (my youngest daughter was there). There can be no doubt that all of us see racism in some form or another everyday—so spatial distance is closed. So, what keeps us quiet?

Its social distance and experiential distance that keeps us from acting. Social distance is closed when there is a shared context whereby people are impacted in similar ways. That simply is just not the case here as those who have been in the minority are consistently treated differently, intentionally or not. Experiential distance is how we experience the ‘transgression’ and certainly, white men like me have had the privilege of getting away with almost everything for a long time—even if our only sin was to sit back and do nothing (the biggest sin of all). The distance here is too great to close and my suggestion is this is why nothing ever changes.

But what if there was something we could do, starting with leaders inside our businesses? What if there were a way to close all four types of psychological distance and make real change happen? There is a way, but it has to happen NOW. Right NOW.

Possible Actions

To close experiential distance, we need to listen to what is going on and understand the differing perspectives without judgment. Just listen, educating ourselves along the way. Perceptions are reality, and the perceptions of the black community are sharing one voice that we must understand. Further, ‘pain empathy’ shows we have the capacity to feel the pain of others neurologically (think how you sort of feel it when you see someone close the car door on their finger) and social pain impacts our brain in similar ways; here we should reach out to our African American friends to fully sense this at deeper levels.

Social distance is harder to close because you have to be impacted in similar ways.

Maybe this idea of ‘walking in their shoes’ is the opportunity to close social distance. It will never be quite the same of course but a step in the right direction. Find a way to become the minority…take on a project for work and move to Africa for example where international business there has gotten much better at ensuring most of their top executives are local. I don’t have the data, but I suspect those of us who have had one or multiple ex-patriate assignments, especially in cultures that are markedly different from our own, have less of a propensity toward racism.

Hiring to get more diverse can happen when you have multiple people profile what is needed on the job and candidates go through various assessments—anonymously–to see if they match that profile. Similarly, promotion decisions get stronger when data is shown highlighting performance against a given context, without looking at who it is…then revealing the short-list of candidates. Only when you realize that one of them is Black, does the bias kick-in…but it’s too late now, especially with a skilled facilitator on the talent team inside your organization at the helm.

There has got to be other ways…what do you think? What ‘critical move’ can you recommend for your company? Make it happen.

1Junger, S. (2016). Tribe: on homecoming and belonging. New York, NY. Hachette Book Group.

2Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations: a guide to creating organizations inspired by the next stage of human consciousness. Brussels: Nelson Parker.

3Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2011). Switch: How to change things when change is hard. Waterville, Me: Thorndike Press.

4Navarro, R. (unknown date). Retrieved from https://diversity.ucsf.edu/resources/unconscious-bias

5Biography.com. Retrieved from https://www.biography.com/news/marilyn-monroe-ella-fitzgerald-friendship

By the way, Sandra Mayes Unger has a book coming out in September called “Tribe” with the subtitle of “why do all our friends look just like us.” Sounds intriguing as she explores some of these same ideas from a different lens.